A study in mice funded by the National Institutes of Health shows for the first time that

A study in mice funded by the National Institutes of Health shows for the first time that

«Reconnecting neurons in the visual system is one of the biggest challenges to developing regenerative therapies for blinding eye diseases like glaucoma," said NEI Director Paul A. Sieving, M.D., Ph. D. «This research shows that mammals have a greater capacity for central nervous system regeneration than previously known.»

The optic nerve is the eye’s data cable, carrying visual information from the

The researchers induced optic nerve damage in mice using forceps to crush the optic nerve of one eye just behind the eyeball. The mice were then placed in a chamber several hours a day for three weeks where they viewed

Prior work by the scientists showed that increasing activity of protein called mTOR promoted optic nerve regeneration. And so they wondered if combining visual stimulation with increased mTOR activity might have a synergistic effect. Two weeks prior to nerve crush, the scientists used gene therapy to cause the retinal ganglion cells to overexpress mTOR. Optic nerve crush was performed and mice were exposed to

«We saw the most remarkable growth when we closed the good eye, forcing the mice to look through the injured eye," said Andrew Huberman, Ph. D., associate professor, Stanford University School of Medicine’s department of neurobiology, and lead author of the report, published online today in Nature Neuroscience. In three weeks, the axons grew as much as 12 millimeters, a rate about 500 times faster than untreated CNS axons.

The regenerating axons also navigated to the correct brain regions, a finding that Huberman said sheds light on a pivotal question in regenerative medicine: «If a nerve cell can regenerate, does it wander or does it recapitulate its developmental program and find its way back to the correct brain areas?»

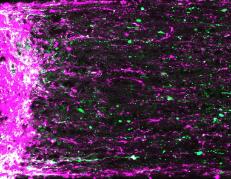

Using transgenic mouse lines designed to express fluorescent proteins only in specific retinal ganglion cell subtypes (about 30 exist), the investigators traced where regenerating axons went. «The two types of retinal ganglion cells that we looked at — α-cells and melanopsin cells — seemed fully capable of navigating back to correct locations in the brain, plugging in and forming synapses," said Huberman. «And just as interesting, they didn’t go to the wrong places." Fluorescent axons appeared in brain regions where α-cells and melanopsin cells would be expected but were absent in other regions.

Visual function was partially restored in animals that received visual/mTOR combination therapy. The investigators used four tests to assess four types of visual perception: ability to track moving objects, pupillary reflex, depth perception, and ability to detect an overhead predator — a stimulus that normally causes mice to freeze or flee for cover. Mice treated with combination therapy performed significantly better than untreated mice in two of the four tests.

«This study’s striking finding that activity promotes nerve regrowth holds great promise for therapies aimed at degenerative retinal diseases," noted Thomas Greenwell, NEI program director for retinal neuroscience research. Greenwell said the research has great relevance to the NEI Audacious Goals Initiative (AGI), a sustained effort to develop regenerative medicine for retinal diseases.

For future therapies that preserve optic nerve axons, Huberman envisions the development of filters for virtual reality video games, television programs, or eyeglasses designed to deliver