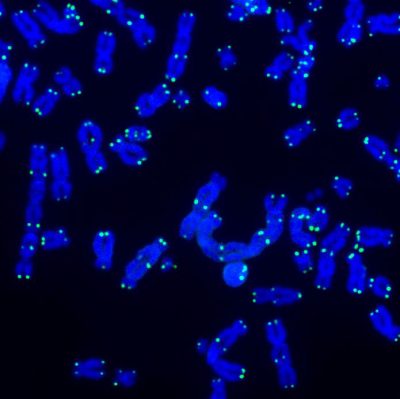

Telomeres protect the ends of chromosomes from damage. This image shows telomeres (green) and DNA (blue) during DNA repair activities.

Telomeres protect the ends of chromosomes from damage. This image shows telomeres (green) and DNA (blue) during DNA repair activities.Click here for a high-resolution image.

Credit: Salk Institute

As we age, the end caps of our chromosomes, called telomeres, gradually shorten. Now, Salk scientists have discovered that when telomeres become very short, they communicate with mitochondria, the cell’s powerhouses. This communication triggers a complex set of signaling pathways and initiates an inflammatory response that destroys cells that could otherwise become cancerous.

The findings, published in Nature on February 8, 2023, could lead to new ways of preventing and treating cancer as well as designing better interventions to offset the harmful consequences of aging.

The discovery is the result of a collaboration between co-senior authors and Salk Professors Jan Karlseder and Gerald Shadel, who teamed up to explore similarities they had each found in inflammatory signaling pathways. Karlseder’s lab studies telomere biology and how telomeres prevent cancer formation. Shadel’s lab studies the role mitochondria play in human disease, aging, and the immune system.

“We were excited to discover that telomeres talk to mitochondria,” says Karlseder, holder of the Donald and Darlene Shiley Chair. “They clearly synergize in well-controlled biological processes to initiate cellular pathways that kill cells that could cause cancer.”

When telomeres shorten to a point where they can no longer protect chromosomes from damage, a process called “crisis” occurs and cells die. This beneficial natural process removes cells with very short telomeres and unstable genomes and is known to be a powerful barrier against cancer formation. Karlseder and the study’s first author Joe Nassour, a senior research associate in the Karlseder lab, previously discovered that cells in crisis are removed by a process called autophagy, in which the body rids itself of damaged cells.

In this study, the team wanted to know how autophagy-dependent cell-death programs are activated during crisis, when telomeres are extremely short. By conducting a genetic screen using human skin cells called fibroblasts, the scientists discovered interdependent immune sensing and inflammatory signaling pathways—similar to the ones by which the immune system combats viruses—that are crucial for cell death during crisis. Specifically, they found that RNA molecules emanating from short telomeres activate immune sensors called ZBP1 and MAVS in a unique way on the outer surface of mitochondria.

In this illustration, shortened telomeres are represented as the ends of the two sparklers. The telomeres sendoff inflammatory communication signals, represented as sparkler paths, to mitochondria. The telomere-to-mitochondria communication activates the immune system which destroys cells that might become cancerous.

Click here for a high-resolution image.

In this illustration, shortened telomeres are represented as the ends of the two sparklers. The telomeres sendoff inflammatory communication signals, represented as sparkler paths, to mitochondria. The telomere-to-mitochondria communication activates the immune system which destroys cells that might become cancerous.

Click here for a high-resolution image.Credit: Salk Institute

The findings demonstrate important links between telomeres, mitochondria, and inflammation and underscore how cells can bypass crisis (thereby evading destruction) and become cancerous when the pathways are not functioning properly.

“Telomeres, mitochondria, and inflammation are three hallmarks of aging that are most often studied in isolation,” says Shadel, holder of the Audrey Geisel Chair in Biomedical Science and director of the San Diego Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in the Basic Biology of Aging. “Our findings showing that stressed telomeres send an RNA message to mitochondria to cause inflammation highlights the need to study interactions between these hallmarks to fully understand aging and perhaps intervene to increase health span in humans.”

“Cancer formation is not a simple process,” says Nassour. “It is a multistep process that requires many alterations and changes throughout the cell. A better understanding of the complex pathways linking telomeres and mitochondria may lead to the development of novel cancer therapeutics in the future.”

Next, the scientists plan to further examine the molecular basis of these pathways and explore the therapeutic potential of targeting these pathways to prevent or treat cancer.

Other authors included Lucia Gutierrez Aguiar, Adriana Correia, Tobias T. Schmidt, Laura Mainz, Sara Przetocka, Candy Haggblom, Nimesha Tadepalle, April Williams, and Maxim N. Shokhirev of Salk, and Semih C. Akincilar and Vinay Tergaonkar of the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, Singapore.

The work was supported by the European Molecular Biology Organization (ALTF 213-216 and ALTF 668-2019), the Hewitt Foundation, the National Cancer Institute (K99CA252447 and P30-014194), the Glenn Foundation for Biology of Aging Research, the Swiss National Science Foundation Early Postdoc Mobility Fellowship (P2ZHP3_195173), the National Institute on Aging (AG073084, AG064049, and AG068635), the National Institutes of Health (RO1CA227934, RO1CA234047, RO1CA228211, RO1AG077324, and R01AR069876), the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, the Auen Foundation, the American Heart Association (19PABHI34610000), and the American Heart Association-Allen Institute (19PABHI34610000).

AUTHORS

Joe Nassour, Lucia Gutierrez Aguiar, Adriana Correia, Tobias T. Schmidt, Laura Mainz, Sara Przetocka, Candy Haggblom, Nimesha Tadepalle, April Williams, Maxim N. Shokhirev, Semih C. Akincilar, Vinay Tergaonkar, Gerald S. Shadel and Jan Karlseder

salk.edu