Macrophages are immune cells at the front line, detecting pathogens and kicking off an inflammatory response when needed. Understanding how macrophages determine when to go all-out and when to keep calm is key to finding new ways to strike the right balance — particularly in cases where inflammation goes too far, such as in sepsis, colitis and other autoimmune disorders.

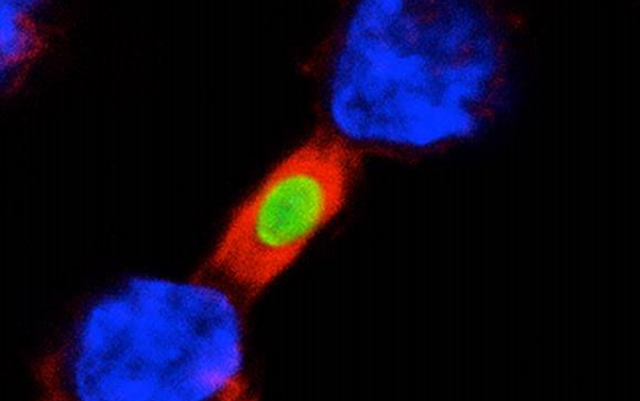

Two macrophages (blue) fighting to engulf the same pathogen (green). GIV/Girdin is shown in red.

In a study published October 14, 2020 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine discovered that a molecule called Girdin, or GIV, acts as a brake on macrophages.

When the team deleted the GIV gene from mouse macrophages, the immune cells rapidly overacted to even small amounts of live bacteria or a bacterial toxin. Mice with colitis and sepsis fared worse when lacking the GIV gene in their macrophages.

The researchers also created peptides that mimic GIV, allowing them to shut down mouse macrophages on command. When treated with the GIV-mimic peptide, the mice’s inflammatory response was tempered.

“When a patient dies of sepsis, he or she does not die due to the invading bacteria themselves, but from an overreaction of their immune system to the bacteria,” said senior author Pradipta Ghosh, MD, professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center. “It’s similar to what we’re seeing now with dangerous ‘cytokine storms’ that can result from infection with the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Macrophages, and the cytokines they produce, are the body’s own immune-stimulating agents and when produced in excessive amounts, they do more harm than good.”

Digging deeper into the mechanism at play, Ghosh and team discovered that the GIV protein normally cozies up to a molecule called Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). TLR4 is stuck right through the cell membrane, with bits poking inside and outside the cell. Outside of the cell, TLR4 is like an antenna, searching for signs of invading pathogens. Inside the cell, GIV is nestled between the receptor’s two “feet.” When in place, GIV keeps the feet apart, and nothing happens. When GIV is removed, the TLR4 feet touch and kick off a cascade of immune-stimulating signals.

Ghosh’s GIV-mimicking peptides can take the place of the protein when it’s missing, keeping the feet apart and calming macrophages down.

“We were surprised at just how fluid the immune system is when it encounters a pathogen,” said Ghosh, who is also director of the Institute for Network Medicine and executive director of the HUMANOID Center of Research Excellence at UC San Diego School of Medicine. “Macrophages don’t need to waste time and energy producing more or less GIV protein, they can rapidly dial their response up or down simply by moving it around, and it appears that such regulation happens at the level of gene transcription.”

Ghosh and team plan to investigate the factors that determine how the GIV brake remains in place when macrophages are resting or is removed to mount a response to a credible threat. To enable these studies, the Institute for Network Medicine at UC San Diego School of Medicine recently received a new $5 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health. Ghosh shares this award with her colleagues Debashis Sahoo, PhD, assistant professor at UC San Diego School of Medicine and Jacobs School of Engineering, and Soumita Das, PhD, associate professor of pathology at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

By Heather Buschman, PhD

ucsdnews.ucsd.edu