Seeking that proverbial needle, scientists at the University of Florida are looking in an unexpected place: the digestive tract of a tiny, translucent worm called Caenorhabditis elegans.

New research published in PLOS Pathogens establishes, for the first time, a link between specific bacteria species and physical manifestations of neurodegenerative diseases. The study’s lead author is Alyssa Walker, a microbiology and cell science doctoral candidate in the UF/IFAS College of Agricultural and Life Sciences.

“Looking at the microbiome is a relatively new approach to investigating what causes neurodegenerative diseases. In this study, we were able to show that specific species of bacteria play a role in the development of these conditions,” said Daniel Czyz, Walker’s dissertation advisor.

Czyz is the senior author of the study and an assistant professor in the UF/IFAS department of microbiology and cell science.

“We also showed that some other bacteria produce compounds that counteract these ‘bad’ bacteria. Recent studies have shown that patients with Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease are deficient in these ‘good’ bacteria, so our findings may help explain that connection and open up an area of future study,” he added.

All neurodegenerative diseases can be traced to problems with the way proteins are handled in the body. If proteins are misfolded, they build up and accumulate in tissues. These protein aggregates, as scientists call them, interfere with cell functioning and lead to neurodegenerative disorders.

Czyz and his co-authors wanted to know if introducing certain bacteria into the C. elegans worms would be followed by protein aggregation in the worms’ tissues.

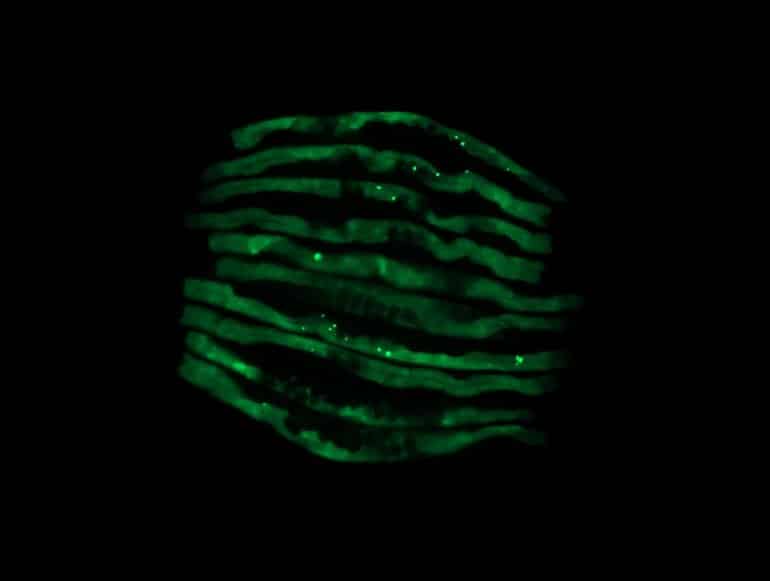

“That is, in fact, what we observed. We have a way of marking the aggregates so they glow green under the microscope. We saw that worms colonized by certain bacteria species were lit up with aggregates that were toxic to tissues, while those colonized by the control bacteria were not,” Czyz said.

“This occurred not just in the intestinal tissues, where the bacteria are, but all over the worms’ bodies, in their muscles, nerves and even reproductive organs.”

Surprisingly, the offspring of affected worms also showed increased protein aggregation — even though these offspring never encountered the bacteria originally associated with the condition.

“This is very interesting because it suggests that these bacteria generate some sort of a signal that can be passed along to the next generation,” Czyz said.

Worms colonized by a non- pathogenic control E. coli. Credit: University of Florida

Worms colonized by the “bad” bacteria also lost mobility, a common symptom of neurodegenerative diseases.

“A healthy worm moves around by rolling and thrashing. When you pick up a healthy worm, it will roll off the pick, a simple device that we use to handle these tiny animals. But worms with the bad bacteria couldn’t do that because of the appearance of toxic protein aggregates,” explained Walker, who developed this assessment method.

“You could compare the pick to an obstacle course: just as a person with a neurodegenerative disease will have trouble getting across, the same is true with these worms, just at a much smaller scale,” Czyz added.

Fun fact: Human eyebrow hairs or eyelashes make for very good picks.

“The worms are very delicate, so you need a tool that won’t damage them. They are also transparent and have a simple body plan. Studies like ours are possible because these worms normally feed on bacteria,” Czyz said.

“The worms are only one millimeter long, and they each have exactly 959 cells,” Czyz said.

“But in many ways, they are a lot like us humans — they have intestines and muscles and nerves, but instead of being composed of billions of cells, each organ is just a handful of cells. They are like living test tubes. Their small size allows us to do experiments in a much more controlled way and answer important questions we can apply in future experiments with higher organisms and, eventually, people.”

Currently the Czyz lab is testing hundreds of strains of bacteria found in the human gut to see how they affect protein aggregation in C. elegans. The group is also investigating how bacteria associated with neurodegeneration cause protein misfolding at the molecular level.

Czyz is also interested in possible connections between antibiotic-resistant bacteria and protein misfolding.

“Almost all of the bacteria we found associated with protein misfolding are also associated with antibiotic-resistant infections in people. However, it will take many more years of research before we can understand what, if any, connection there is between antibiotic resistance and neurodegenerative diseases,” Czyz said.

Contact: Samantha Murray – University of Florida

neurosciencenews.com