Philip Guo caught the coding bug in high school, at a fairly typical age for a Millennial. Less typical is that the UC San Diego cognitive scientist is now eager to share his passion for programming with a different demographic. And it’s not one you’re thinking of — it’s not elementary or middle

In the first known study of older adults learning computer programming, Guo outlines his reasons: People are living and working longer. This is a growing segment of the population, and it’s severely underserved by

«Computers are everywhere, and digital literacy is becoming more and more important," said Guo, assistant professor in the Department of Cognitive Science, who is also affiliated with UC San Diego’s Design Lab and its Department of Computer Science and Engineering. «At one time, 1,000 years ago, most people didn’t read or write — just some monks and select professionals could do it. I think in the future people will need to read and write in computer language as well. In the meantime, more could benefit from learning how to code.»

Guo’s study was recently awarded honorable mention by the world’s leading organization in

When prior

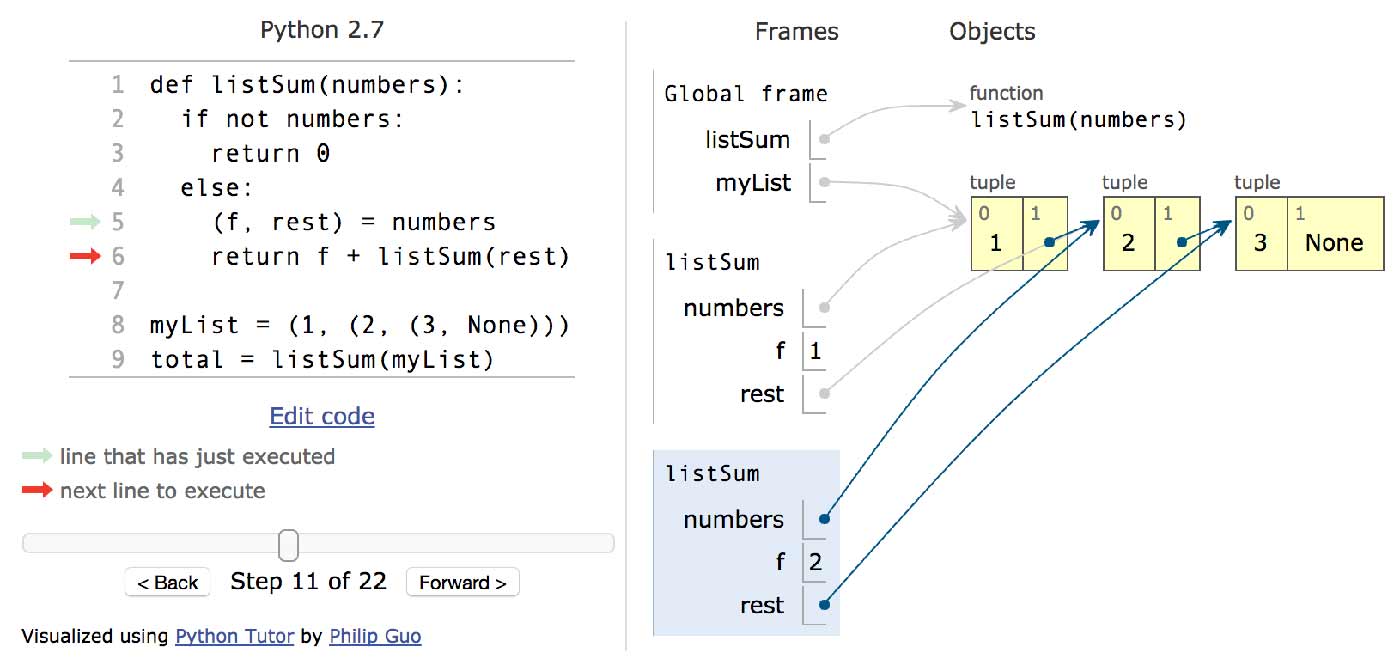

The Python Tutor tool at work, showing code and diagrams. Courtesy Philip Guo

The Study

For his study, Guo surveyed users of pythontutor.com. A

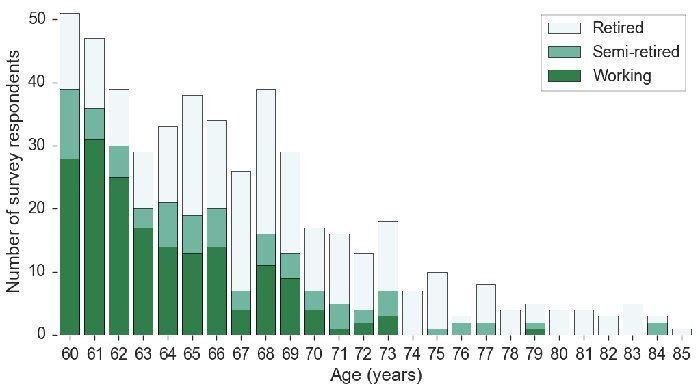

Guo’s survey included 504 people between the ages of 60 and 85, from 52 different countries. Some were retired and

What Guo discovered: Older adults are motivated to learn programming for a number of reasons. Some are

Reasons not related to age include seeking continuing education for a current job (14 percent) and wanting to improve future job prospects (9 percent). A substantial group is in it just for personal enrichment: 19 percent to implement a specific hobby project idea, 15 percent for fun and entertainment, and 10 percent out of general interest.

Interestingly, 8 percent said they wanted to learn to teach others.

Topping the list of frustrations for older students of coding was bad pedagogy. It was mentioned by 21 percent of the respondents and ranged from the use of jargon to sudden spikes in difficulty levels. Lack of

Guo surveyed adults between the ages of 60 and 85 who were users of pythontutor.com and learning how to code. They were mix of retired, semi-retired and still working.

Other frustrations included a perceived decline in cognitive abilities (12 percent) and no human contact with tutors and peers (10 percent).

The study’s limitations are tied in part to the instrument —

The Implications

Based on this first set of findings and using a

Just as it’s key to understand who the learners are so is understanding where they have trouble. Repetition and frequent examples might be good to implement, as well as more

Context matters, too. Lessons are more compelling when they are put into domains that people personally care about. And Guo recommends coding curricula that enable older adults to tell their life stories or family histories, for example, or write software that organizes health information or assists

Guo, who is currently working on studies to extend coding education to other underrepresented groups, advocates a computing future that is fully inclusive of all ages.

«There are a number of social implications when older adults have access to computer programming — not merely computer literacy," he said. «These range from providing engaging mental stimulation to greater gainful employment from the comfort of one’s home.»

By moving the tech industry away from its current focus on youth, Guo argues, we all stand to gain.

Source: http://ucsdnews.ucsd.edu/pressrelease/geeking_out_in_the_golden_years