The condition, called fragile X, has devastating effects on intellectual abilities.

Fragile X affects one boy in 4,000 and one girl in 7,000. It is caused by a mutation in a gene that fails to make the protein FMRP. In 2011, Xinyu Zhao, a professor of neuroscience, showed that deleting the gene that makes FMRP in a region of the brain that is essential to memory formation caused memory deficits in mice that mirror human fragile X.

Xinyu Zhao

Tantalizingly, Zhao’s 2011 study showed that reactivating production of FMRP in new neurons could restore the formation of new memories in the mice. But what remained unclear was exactly how the absence of FMRP was blocking neuron formation, and whether there was any practical way to avert the resulting disability.

Now, in a study published on April 27 in Science Translational Medicine, Zhao and her colleagues at the Waisman Center at

This study’s newfound understanding of the biochemical chain of events became the basis for identifying an experimental cancer drug called

In the new study, mice with the FMRP deletion took

Statistically, the memory capacities of normal mice and fragile X models that were treated with

Still, many hurdles remain before the advance can be tested on human patients, Zhao says. «We are a long way from declaring a cure for fragile X, but these results are promising.»

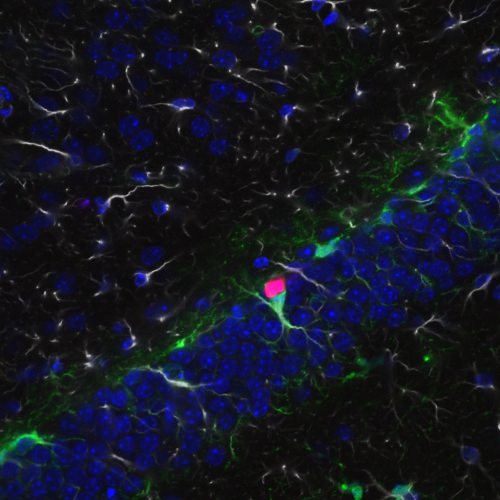

This image from a confocal microscope shows neural stem cells (green) in the mouse hippocampus that are actively proliferating because they express Ki67 (red), a protein that is only present in proliferating cells.

The mouse memory test relied on curiosity. «We placed two objects in an enclosure and let the mice run around," Zhao says. «Mice are naturally curious, so they explore and sniff each one. We take them out after 10 minutes, replace one object with a different one, wait 24 hours and put the mouse back in. If the mouse has normal learning ability, it will recognize the new object and spend more time with it. Mice without the FMRP gene don’t remember the old object, so they spend a similar amount of time on each one.»

The behavioral assessment was done by different people, says Zhao. «First author Yue Li, a postdoctoral researcher at Waisman, ran the test and sent the video to Michael Stockton, an undergraduate working on the project." Stockton timed how and where each mouse was exploring, «but he had no idea which mouse was which," Zhao says. «It was fantastic to see such clear data.»

Two other undergraduates, Jessica Miller and Ismat Bhuiyan (who is now in graduate school) and postdoctoral fellows Brian Eisinger and Yu Gao also worked on the study. The Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation has applied for a patent on the discovery.

The dose used in the trial — only 10 percent of the dose proposed for cancer chemotherapy — caused no apparent harm, she says. «We measured body weight and activity. So far, the mice look healthy and happy.»

Because more than

In any case, it’s far too soon to declare victory over fragile X, Zhao stresses. «There are many hurdles. Among the many questions that need to be answered is how often the treatment would be needed. Still, we’ve drawn back the curtain on fragile X a bit, and that makes me optimistic.»

Source: http://news.wisc.edu/experimental-drug-cancels-effect-from-key-intellectual-disability-gene-in-mice/