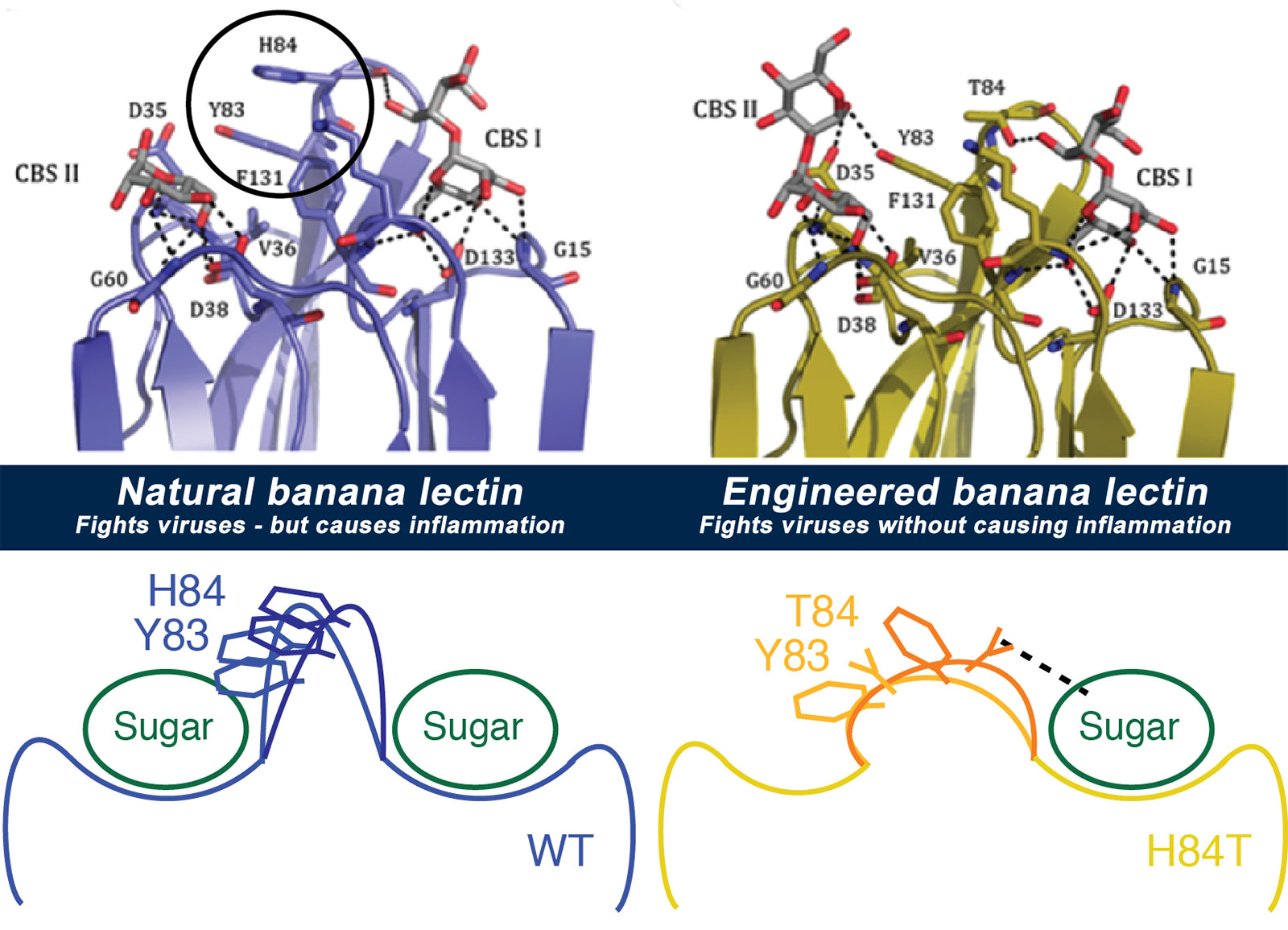

By studying the banana lectin molecule (top left) and what made it bind to both viruses and immune system cells (bottom left), the team was able to figure out how to change the way cells bind to it, to make a new version (top right) that still binds viruses but doesn't cause inflammation (bottom right).

The new research focuses on a protein called banana lectin, or BanLec, that «reads» the sugars on the outside of both viruses and cells. Five years ago, scientists showed it could keep the virus that causes AIDS from getting into

Now, in a new study published in the journal Cell, an international team of scientists reports how they created a new form of BanLec that still fights viruses in mice, but doesn’t have a property that causes irritation and unwanted inflammation.

They succeeded in peeling apart these two functions by carefully studying the molecule in many ways, and pinpointing the tiny part that triggered side effects. Then, they engineered a new version of BanLec, called H84T, by slightly changing the gene that acts as the instruction manual for building it.

The result: a form of BanLec that worked against the viruses that cause AIDS, hepatitis C and influenza in tests in tissue and blood

«What we’ve done is exciting because there is potential for BanLec to develop into a broad spectrum antiviral agent, something that is not clinically available to physicians and patients right now," said

A global project tackles a global problem

The 26 scientists on the

They used a wide range of scientific

Their efforts helped them understand how BanLec connects to both viruses and to sugar molecules on the outside of cells, and how it leads to irritation and other side effects by triggering signals that call in the «first responders» of the body’s immune system.

This understanding is what allowed them to change the gene in a way that

The new version of BanLec has one less tiny spot on its surface for sugars to attach, called a «Greek key» site. This makes it impossible for sugars on the surface of immune system cells called T cells to attach in multiple spots at once and trigger inflammation. But it still allows BanLec to grab on to sugars on the surface of viruses and keep them from getting into cells.

Several years of research still lie ahead before BanLec can be tested in humans. But Markovitz and

«Better flu treatments are desperately needed," said Markovitz, who treats patients with infectious diseases at the

The team continues to test H84T BanLec against other viruses in mice and tissue samples.

Cracking the sugar code

Even while work on H84T BanLec continues, the team’s achievement in engineering a lectin molecule opens doors to other work on other lectins. Lectin molecules read the sugar code of sugar molecules that cover the surface of many viruses and cells.

Even while work on H84T BanLec continues, the team’s achievement in engineering a lectin molecule opens doors to other work on other lectins. Lectin molecules read the sugar code of sugar molecules that cover the surface of many viruses and cells.

Scientists still don’t fully understand all the things that the sugar code

Sugars, and the lectins that attach to them, seem to play a key role in how cells «talk» to one another, call for help, and perform other functions.

In fact, one of the mysteries remaining for BanLec work is just how the T cells of the immune system actually attach to it.

Markovitz also notes that

An important part of the work to decode the structure of the BanLec molecules was done by Jeanne Stuckey and Jennifer Meagher of the Center for Structural Biology at the

Funding for the work included National Institutes of Health grants to