For people exposed to TB, the biggest risk factor for infection is exposure to smoke, including active and passive cigarette smoking and smoke from burning fuels. This risk is even greater than

When TB enters the body, the first line of defence it encounters is a specialist immune cell known as a macrophage (Greek for ‘big eater’). This cell engulfs the bacterium and tries to break it down. In many cases, the macrophage is successful and kills the bacterium, preventing TB infection, but in some cases TB manages not just to avoid destruction, but to use macrophages as ‘taxi cabs’ and get deep into the host, spreading the infection. TB’s next step is to cause infected macrophages to form

An international team of researchers, led by the University of Cambridge, and the University of Washington, Seattle, studying genetic variants that increase susceptibility to TB in zebrafish — a ‘

The key, the researchers found, lay in a second property of the macrophage: housekeeping. As well as destroying bacteria, the macrophage also recycles unwanted material from within the body for reuse, and these lysosomal deficiency disorders were preventing this essential operation.

Professor Lalita Ramakrishnan from the Department of Medicine at the University of Cambridge, who led the research, explains: «Macrophages act a bit like vacuum cleaners, hoovering up debris and unwanted material within the body, including the billions of cells that die each day as part of natural turnover. But the defective macrophages are unable to recycle this debris and get clogged up, growing bigger and fatter and less able to move around and clear up other material.

«This can become a problem in TB because once the TB granuloma forms, the host’s best bet is to send in more macrophages at a slow steady pace to help the already infected macrophages.»

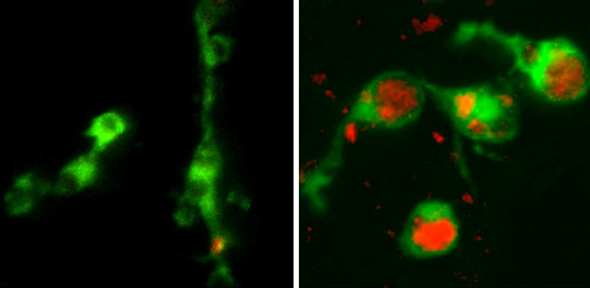

Image: Left — normal macrophages (green); Right — dysfunctional macrophages whose lysosomes (red) are clogged with cell debris. Credit: Steven Levitte

«When these distended macrophages can’t move into the TB granuloma," adds

The researchers looked at whether the effect seen in the lysosomal deficiency disorders, where the

«We saw that accumulation of material inside of macrophages by many different means, both genetic and acquired, led the same result: macrophages that could not respond to infection," explains

This discovery then led the team to see whether the same phenomenon occurred in humans. Working with Professor Joe Keane and his colleagues from Trinity College Dublin, the researchers were able to show that the macrophages of smokers were similarly clogged up with smoke particles, helping explain why people exposed to smoke were at a greater risk of TB infection.

«Macrophages are our best shot at getting rid of TB, so if they are slowed down by smoke particles, their ability to fight infection is going to be greatly reduced," says Professor Keane. «We know that exposure to cigarette smoke or smoke from burning wood and coal, for example, are major risk factors for developing TB, and our finding helps explain why this is the case. The good news is that stopping smoking reduces the risk — it allows the impaired macrophages to die away and be replaced by new, agile cells.»

Image:

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Wellcome Trust, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), the Health Research Board of Ireland and The Royal City of Dublin Hospital Trust.

Also contributing to this research were Professor David Tobin from Duke University, Dr Cecilia Moens from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Institute, Drs

Source: http://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/clogged-up-immune-cells-help-explain-smoking-risk-for-tb