The last time you had a stomach bug, you probably didn’t feel much like eating. This loss of appetite is part of your body’s normal response to an illness but is not well understood. Sometimes eating less during illness promotes a faster recovery, but other

Now, research from the Salk Institute shows how bacteria block the appetite loss response in their host to both make the host healthier and also promote the bacteria’s transmission to other hosts. This surprising discovery, published in the journal Cell on January 26, 2017, reveals a link between appetite and infection and could have implications in treating infectious diseases, infection transmission and appetite loss associated with illness, aging, inflammation or medical interventions (like chemotherapy).

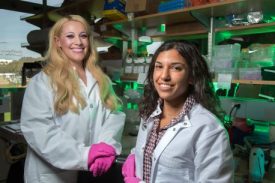

«It’s long been known that infections cause loss of appetite but the function of that, if any, is only beginning to be understood," says Janelle Ayres, assistant professor at Salk Institute’s Nomis Foundation Laboratories for Immunobiology and Microbial Pathogenesis.

Mice orally infected with the bacteria Salmonella Typhimurium typically experience appetite loss and eventually become much sicker as the bacteria become more

Mice orally infected with the bacteria Salmonella Typhimurium typically experience appetite loss and eventually become much sicker as the bacteria become more

The finding was initially puzzling: why would the bacteria become less virulent and not spread to other areas in the body when nutrients were more plentiful? And why would Salmonella actively promote this condition? It turns out the bacteria were making a tradeoff between virulence, which is the ability of a microbe to cause disease within one host, and transmission, which is its ability to spread and establish infections between multiple hosts.

«What we found was that appetite loss makes the Salmonella more virulent, perhaps because it needs to go beyond the intestines to find nutrients for itself. This increased virulence kills its host too fast, which compromises the bacteria’s ability to spread to new hosts," explains Sheila Rao, a Salk research associate and the first author on the study. «The tradeoff between transmission and virulence has not been appreciated

When the host ate more and survived longer during infection, the Salmonella benefitted: bacteria in those mice were able to spread via feces to other animals and increase its transmission between hosts, as compared to bacteria in mice who didn’t eat and died sooner due to heightened bacterial virulence.

The researchers discovered that, to halt the

The researchers discovered that, to halt the

Though the same

«Now that we’d identified this mechanism that regulates appetite, we want to turn it on the flip side and see if we can decrease appetite via this mechanism to help in cases of metabolic disease," says Ayres.

The discovery also points to the tantalizing possibility of treating infectious diseases with approaches other than antibiotics, such as nutritional intervention. «Finding alternatives to antibiotics is incredibly important as these drugs have already encouraged the evolution of deadly

Other researchers on the study were Alexandria M. Palaferri Schieber, Carolyn P. O’Connor, Mathias Leblanc and Daniela Michel of the Salk Institute.

The work and the researchers involved were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the Nomis Foundation, the Searle Scholar Foundation and the Ray Thomas Edward Foundation.

Source: http://www.salk.edu/news-release/feed-cold-starve-fever-not-fast-according-salk-research/